llama2.npy : Implementing Llama2 LLM using just Python and Numpy

Large Language Models (LLMs), such as GPT-4, Claude, and Llama2, have reshaped the landscape of Natural Language Processing (NLP), democratizing AI applications. These models often have billions of parameters and are trained on massive datasets of text, often crawled from the internet.

Recently Andrej Karpathy released a github repository called llama2.c, in which he implements the architecture of Llama2 LLM at various scales, and has a custom built inference code written completely in C. Taking inspiration from that, contributors have created/ported their own Llama2 inference code to different languages.

In this blog post, I will cover my own implementation in github called llama2.npy where I port llama2.c to do inference using only Python and Numpy. I will go through the basics of the Llama2 architecture and the main modules of the inference pipeline like the tokenizer, attention, positional embeddings and the text generator.

- Llama2 Architecture

- Byte Pair Encoding Tokenizer

- Attention

- Rotary Position Embedding (RoPE)

- Text Generation

Most of the porting was straightforward due to similarities of the PyTorch and Numpy APIs, but there needed to be some custom implementation done for incompatible functionalities, Neural Network Layers and Normalizers. Further, some work was needed to implement a custom tokenizer and model weight loading functionalities. Throughout the process, I also simpliflied the code where needed.

Llama2 Architecture

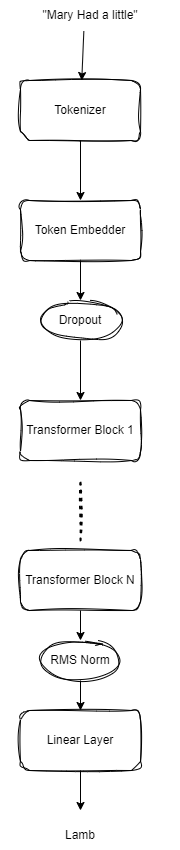

The Llama2 architecture is portrayed in the figure below:

The Llama2 architecture is fairly simple and modular and contains the following modules:

- Tokenization: The input text is first tokenized, then converted to unique representations (ids) using a Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) tokenizer.

- Token Embedding: The token ids are then fed into a token embedder to get token embeddings, which are then passed through a dropout layer to get token embeddings.

- Transformer Blocks: The token embeddings are then fed into layers of Transformer Blocks which consist of RMS Norms,Attention, Rotary Positional Embeddings and Feed Forwards Networks.

- Output Projection: The final output from the transformer blocks is fed through a RMS Norm layer into a linear layer to get the output.

- Autoregressive Sampling: To get a sentence completion we autoregressivley feed the network’s output into itself to keep generating new tokens.

Implementation Specific Deviations:

- No KV-Caching: In this implementation we do naive sampling without any KV-caching, which is inefficient in practice.

- Weight Tying: The weights of the token embedder and the output linear layer are shared. This is for increased efficiency and better convergence of our smaller model.

Now let’s explore the important parts of this architecture one by one.

Byte Pair Encoding Tokenizer

Neural Networks operate on numerical data, they multiply numbers. But then how do language models like Llama2 or GPT understand the text we write ?

The key lies in the use of Tokenizers, specialized modules that convert text into a set of tokens, that then we can represent using numerical ids for processing by NLP models.

An ideal tokenizer would convert text into unique ids while keeping the possible number of representations small and meaningful.

The most popular approaches to tokenization involve:

- Character based tokenizers: Map each character in the vocabulary to an unique representation.

- Word based tokenizers: Map each individual word in the vocabulary to an unique representation.

- Subword based tokenizers: Create a vocabulary of subwords using some method. Split words into subwords that are then mapped to unique representations.

Llama2 relies on one such subword tokenization method called Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE).

To create a subword vocabulary from a given string of text using Byte-Pair encoding, we follow the following steps:

- Initialize: Start with a vocabulary of individual characters or subwords.

- Tokenize: Break the text into characters or subwords.

- Count pairs: Count the frequency of pairs of consecutive characters or subwords.

- Merge: Merge the most frequent pair into a single token and update the vocabulary.

- Repeat: Iterate the above steps until the desired vocabulary size is reached or no more merges can be made.

Now, for Llama2, such a vocabulary is already created, so we can just download and use that. The vocabulary contains a mapping from bytestrings to token_ids as well as scores for each token_id representing how frequent they were in the training set.

The only thing we need to write is a Python class with the logic to:

- Encode a given text into token_ids, using the saved vocabulary

- Decode a list of token ids into text

Below is the Python class I implemented to these:

# Create a Tokenizer class that will be used to tokenize the input text

import struct

import sys

import numpy as np

class Tokenizer():

def __init__(self, model_path: str, vocab_size = 32000) -> None:

self.vocab_size = vocab_size

# Load the tokenizer, store in dicts for fast lookup

self.vocab2index, self.vocab_score2index = self._load_tokenizer(model_path)

self.index2vocab = {v: k for k, v in self.vocab2index.items()}

self.index2vocab_score = {v: k for k, v in self.vocab_score2index.items()}

# An internal function called _load_tokenizer, takes str input, outputs a tuple (dict, dict, int)

def _load_tokenizer(self, model_path: str) -> tuple:

max_token_length = 0

self.vocab2index = {}

self.vocab_score2index = {}

with open(model_path, 'rb') as file:

max_token_length = struct.unpack('i', file.read(4))[0]

for i in range(0, self.vocab_size):

score = struct.unpack('f', file.read(4))[0]

str_len = struct.unpack('i', file.read(4))[0]

bytestr = file.read(str_len)

if type(bytestr) is not str:

bytestr = bytestr.decode('utf8')

self.vocab2index[bytestr] = i

self.vocab_score2index[score] = i

return self.vocab2index, self.vocab_score2index

def encode(self, initial_string: str, bos: bool, eos: bool) -> list:

# Encode the initial string character by character, assunes all characters are in vocab

tokens = [self.vocab2index[char] for char in initial_string]

# Merge consecutive pairs of tokens based on vocab_scores, stop when merging no longer increases the score

while True:

best_score = np.NINF

best_id = -1

best_idx = -1

# Iterate over all consecutive pairs of tokens

for i in range(len(tokens) - 1):

# Convert the pair of tokens into a string

string = self.index2vocab[tokens[i]] + self.index2vocab[tokens[i + 1]]

# Get the ID of this merged string in vocab

str_id = self.vocab2index.get(string, None)

if str_id is not None:

if self.index2vocab_score[str_id] > best_score:

# We found a better pair to merge

best_score = self.index2vocab_score[str_id]

best_id = str_id

best_idx = i

if best_idx == -1:

break # We couldn't find any more pairs to merge, so we're done

# Merge the consecutive pair (best_idx, best_idx+1)

# Replace token at position best_idx with best_id of the merged pair

tokens[best_idx] = best_id

# Delete token at position best_idx+1

tokens = tokens[0:best_idx + 1] + tokens[best_idx + 2:]

return tokens

def decode(self, pt_tokens: list) -> str:

# Convert the list of token IDs back into a string

text = ''.join([self.index2vocab[token] for token in pt_tokens])

return text

In this code the Tokenizer class is desinged for BPE tokenization. It includes methods for loading the tokenizer vocabulary (with scores), encoding a given string, and decoding a list of token IDs back into the original text.

The encoding processing is similar to the BPE encoding described above, with the difference being instead of calculating token frequency at each iteration, we get token scores from the saved vocbalary. Based on these scores, we decide whether to merge subwords a pair of subwords and represent them using a single token or keep using separate tokens for them.

Transformer Block

Now once we have token ids we forward them through standard text embedding and dropout layers to get text embeddings. These are then passed through multiple transformer blocks.

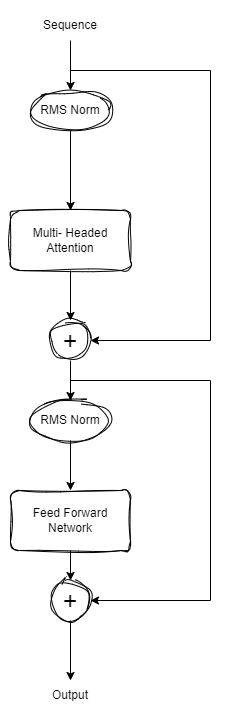

A transformer block has the following architecture:

A transformer block passes the input through an multi headed self attention layer followed by an feed forward layer both with RMS norms and skip connections. The feed forward layer has SiLU activations. The attention module also incorporates Rotary Positional Embedding to take into account position of tokens in a text during attention.

Attention

Attention is a mechanism for our model to incorporate influence of other related tokens in a sequence when encoding a specific token. Self attention is simply the case where the input and output sequences are the same.

For e.g. in the sentence “Sam has a big house”, “big” is associated more with “house” than with “Sam”.

To learn about Attention, let’s first start with the simpler single-headed attention, and then we will move to discuss the multi-headed variant.

Single Headed Attention

We calculate a single headed self-attention output for a sequence by the following steps:

-

Embed and Pack: Calculate emebdding $x_i$ for each token at $i$-th position in the sequence, and pack them together to get the embedded matrix $X$.

-

Calculate Query, Key, Value Matrices: Calculate Query, Key, Value matrices $Q$, $K$ and $V$ by the following equations:

\(Q = X \times W^Q\)

\(K = X \times W^K\)

\(V = X \times W^V\) -

Calculate Scores and apply causal mask: We can get a score matrix containing scores for each token with respect to other tokens by using the equation:

\(S = Q \times K^T\)

However, this would mean tokens are also influenced by tokens occuring after them in the sequence. If we want a causal model where the model only calculates the next token based on previous tokens, we can add an upper triangle mask to the score matrix.

\(S_{masked} = S + Mask\)

where $Mask$ is a upper triangle matrix with $0s$ in valid places and negative infinity in places we don’t want to attend. These negative infinities will resolve to $0s$ after $softmax$ in the next step. -

Calculate Output Encodings: We get the final encoding for each token using the equation

\(Z = softmax(\frac{S_{masked}}{\sqrt{d_k}}) \times V\)

where $i$-th row contains encoding for $i$-th token, and $d_k$ is the dimension of the key vector.

Essentially these matrices represent the following:

- Query: What the tokens are looking for in other tokens.

- Key: What these token offer as influence to other tokens.

- Value: What these tokens actually contain.

The weight matrices $W^{Q}$, $W^{K}$, $W^{V}$ are learned during the model training.

Multi-Headed Attention

In the multi headed case, we just maintain multiple weight matrices $ W_{i}^{Q} , W_{i}^{K}, W_{i}^{V} $ and hence for each attention block, we can go through the attention process multiple times with different weight matrices. This way we generate multiple encodings $ Z_{i} $ where $i$ goes from $0$ to $n - 1$ with $n$ being the number of heads.

At the end we get the final encoding matrix $Z$ for the sequence by just concatenating all the $Z_i$ matrices and multiplying them with a matrix $W^0$.

Below is the python class implementing Multi-headed attention:

class Attention():

def __init__(self, args: ModelArgs):

super().__init__()

self.n_kv_heads = args.n_heads if args.n_kv_heads is None else args.n_kv_heads

self.n_local_heads = args.n_heads

self.n_local_kv_heads = self.n_kv_heads

self.n_rep = self.n_local_heads // self.n_local_kv_heads

self.head_dim = args.dim // args.n_heads

self.wq = NumpyLinear(args.dim, args.n_heads * self.head_dim, bias=False)

self.wk = NumpyLinear(args.dim, self.n_kv_heads * self.head_dim, bias=False)

self.wv = NumpyLinear(args.dim, self.n_kv_heads * self.head_dim, bias=False)

self.wo = NumpyLinear(args.n_heads * self.head_dim, args.dim, bias=False)

self.attn_dropout = NumpyDropout(args.dropout)

self.resid_dropout = NumpyDropout(args.dropout)

self.dropout = args.dropout

# create causal attention mask

mask = np.full((1, 1, args.max_seq_len, args.max_seq_len), float("-inf")).astype(np.float32)

mask = np.triu(mask, k=1).astype(np.float32)

self.mask = mask

def forward(

self,

x: np.ndarray,

freqs_cos: np.ndarray,

freqs_sin: np.ndarray,

):

bsz, seqlen, _ = x.shape

# QKV

xq, xk, xv = self.wq(x), self.wk(x), self.wv(x)

xq = xq.reshape(bsz, seqlen, self.n_local_heads, self.head_dim)

xk = xk.reshape(bsz, seqlen, self.n_local_kv_heads, self.head_dim)

xv = xv.reshape(bsz, seqlen, self.n_local_kv_heads, self.head_dim)

# RoPE relative positional embeddings

xq, xk = apply_rotary_emb(xq, xk, freqs_cos, freqs_sin)

# grouped multiquery attention: expand out keys and values

xk = repeat_kv(xk, self.n_rep) # (bs, seqlen, n_local_heads, head_dim)

xv = repeat_kv(xv, self.n_rep) # (bs, seqlen, n_local_heads, head_dim)

# make heads into a batch dimension

xq = np.transpose(xq, (0,2,1,3)) # (bs, n_local_heads, seqlen, head_dim)

xk = np.transpose(xk, (0,2,1,3))

xv = np.transpose(xv, (0,2,1,3))

# manual implementation

scores = np.matmul(xq, np.transpose(xk, (0,1,3,2))) / np.sqrt(self.head_dim)

scores = scores + self.mask[:, :, :seqlen, :seqlen] # (bs, n_local_heads, seqlen, cache_len + seqlen)

scores = numpy_softmax(scores, axis=-1)

scores = self.attn_dropout(scores)

output = np.matmul(scores, xv) # (bs, n_local_heads, seqlen, head_dim)

# restore time as batch dimension and concat heads

output = np.transpose(output, (0,2,1,3)).reshape(bsz, seqlen, -1)

# final projection into the residual stream

output = self.wo(output)

output = self.resid_dropout(output)

return output

In this code we:

- Calculate the Query, Key, Value matrices

- Apply RoPE embedding

- Calculate scores by using Query and Keys, and apply causal mask and dropout.

- Calculate encoded matrices $Z_i$ using scores and the head dimension.

- Calculate final output $Z$ by multiplying concatenated $Z_i$ matrices with weight $W_0$

- Return the final output after passing through a dropout.

If you want to learn more about attention and how it works in detail, I would recommend checking out the excellent The Illustrated Transformer blog post by Jay Alammar.

Rotary Position Embedding (RoPE)

Attention as we saw above allows token encodings to be influenced by other tokens. However, this influence as we discussed above doesn’t take into account the position of the influencing tokens. Ideally for e.g. tokens far away in the sequence should have different level of influence than tokens right next to each other.

This kind of additional information can be added to the token embeddings before or during the attention process, by using positional embeddings. Llama 2 uses one such positional embedding called Rotary Positional Embedding (RoPE). It was first introduced by Su et al[5] in the RoFormer paper.

Specifically, given two token embeddings $x_i$ and $x_j$, we do RoPE embedding by:

-

Getting the query, key vectors $q_i$ and $k_j$ from them using weight matrices.

-

Then encoding the positional information between them by rotating both the vectors by using a predefined rotation matrix $R^d_{\Theta,m}$ where $m$ is the position of the token being encoded, $\Theta \in \mathbb{R}^{d/2}$ is a preset constant defined as $\Theta = \{ \theta_i = {10000}^{-2(i-1)/d}, i \in [1,2, \dots, d/2] \} $, and $d$ is the dimension of the key, query vectors. The rotation matrix $R^d_{\Theta,m}$ has the formulation: \(R^d_{\theta,m}x = {\begin{pmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\x_3 \\ x_4 \\ \vdots \\ x_{d-1} \\ x_d \end{pmatrix}} \otimes {\begin{pmatrix} \cos m \theta_1 \\ \cos m \theta_1 \\ \cos m \theta_2 \\ \cos m \theta_2 \\ \vdots \\ \cos m \theta_{d/2} \\ \cos m \theta_{d/2} \end{pmatrix}} + {\begin{pmatrix} -x_2 \\ x_1 \\ -x_4 \\ x_3 \\ \vdots \\ -x_d \\ x_{d-1} \end{pmatrix}} \otimes {\begin{pmatrix} \sin m \theta_1 \\ \sin m \theta_1 \\ \sin m \theta_2 \\ \sin m \theta_2 \\ \vdots \\ \sin m \theta_{d/2} \\ \sin m \theta_{d/2} \end{pmatrix}}\)

Essentially for the key, query vectors we rotate their elements two at a time. -

After this applying the softmax calculation and multiplying with value matrix as normal.

Below is the python implementation of RoPE embeddings

def precompute_freqs_cis(dim: int, end: int, theta: float = 10000.0):

freqs = 1.0 / (theta ** (np.arange(0, dim, 2)[: (dim // 2)].astype(np.float32) / dim))

t = np.arange(end).astype(np.float32)

freqs = np.outer(t, freqs).astype(np.float32)

freqs_cos = np.cos(freqs)

freqs_sin = np.sin(freqs)

return freqs_cos, freqs_sin

def apply_rotary_emb(

xq: np.ndarray,

xk: np.ndarray,

freqs_cos: np.ndarray,

freqs_sin: np.ndarray,

) -> Tuple[np.ndarray, np.ndarray]:

# reshape xq and xk to match the complex representation

xq_reshaped = xq.astype(np.float32).reshape(xq.shape[:-1] + (-1, 2))

xq_r = xq_reshaped[..., 0]

xq_i = xq_reshaped[..., 1]

xk_reshaped = xk.astype(np.float32).reshape(xk.shape[:-1] + (-1, 2))

xk_r = xk_reshaped[..., 0]

xk_i = xk_reshaped[..., 1]

# reshape freqs_cos and freqs_sin for broadcasting

freqs_cos = reshape_for_broadcast(freqs_cos, xq_r)

freqs_sin = reshape_for_broadcast(freqs_sin, xq_r)

# apply rotation using real numbers, this is similar to rotating a vector theta degrees using the euler notation

xq_out_r = xq_r * freqs_cos - xq_i * freqs_sin # Real part of rotated vectors

xq_out_i = xq_r * freqs_sin + xq_i * freqs_cos # Imaginary part of rotated vectors

xk_out_r = xk_r * freqs_cos - xk_i * freqs_sin # Real part of rotated vectors

xk_out_i = xk_r * freqs_sin + xk_i * freqs_cos # Imaginary part of rotated vectors

# flatten the last two dimensions

xq_out = np.stack([xq_out_r, xq_out_i], axis=-1).reshape(xq.shape[:3] + (-1,))

xk_out = np.stack([xk_out_r, xk_out_i], axis=-1).reshape(xk.shape[:3] + (-1,))

return xq_out.astype(xq.dtype), xk_out.astype(xk.dtype)

In this implementation, we do RoPE encoding in the following steps:

-

Precompute the Cos and Sin vectors: We precompute the $\cos$ and $\sin$ vectors in the $R^d_{\Theta,m}$ formulation for all positions in dimension $d$.

- Reshape Key, Query vectors: Represent the key and query vectors as complex numbers by reshaping them.

- Rotate Key, Query vectors: Rotate the key, query vectors by applying rotation in the euler form.

- Flatten and return: Flatten the rotated vectors so that they regain their original shape and return.

Text Generation

Once the network is built and trained, we need to be able to prompt it to generate text. This is usually done by inputing an initial text snippet to the network, and then autoregressively generating new tokens.

To generate n tokens given a sequence we do the following:

- Logits for next token: Pass the initial prompt + any tokens generated till now to the model, and get model logits for the next token.

-

Sample new token: Based on the logits, we pick the next token by sampling. There two ways we can go about this:

2.1. No temperature: If no temperature parameter is given for the generation, use the logits as probabilities, and sample the next token

2.2 Temperate and Top_K: Divide logits by the temperature. Then (optionally) filter to only the top_k token indices by value for more efficient sampling. Finally, convert the rescaled logits to probabilities using softmax and sample.

- Append and Repeat: Append the new token to the sequence and repeat steps 1-3 until the number of tokens generated equals n.

Below is the python implementation of text generation function:

def generate(self, idx, max_new_tokens, temperature=1.0, top_k=None):

"""

Autoregressively feed the model the promt + generated tokens at each step.

This is a naive implementation without Key, Value cache.

"""

for _ in range(max_new_tokens):

# if the sequence context is growing too long we must crop it at block_size

idx_cond = idx if idx.size <= self.params.max_seq_len else idx[:, -self.params.max_seq_len:]

# forward the model to get the logits for the index in the sequence

logits = self(idx_cond)

logits = logits[:, -1, :] # crop to just the final time step

if temperature == 0.0:

# "sample" the single most likely index

_, idx_next = numpy_topk_by_partition(logits, k=1, axis=-1)

else:

# pluck the logits at the final step and scale by desired temperature

logits = logits / temperature

# optionally crop the logits to only the top k options

if top_k is not None:

v, _ = numpy_topk_by_partition(logits, k=min(top_k, logits.size(-1)), axis=-1)

logits[logits < v[:, [-1]]] = -float('Inf')

# apply softmax to convert logits to (normalized) probabilities

probs = numpy_softmax(logits, axis=-1)

# sample from the distribution

idx_next = np.random.choice(self.params.vocab_size, p=probs.squeeze())

# append sampled index to the running sequence and continue

idx = np.concatenate((idx, np.array([idx_next]).reshape(1,-1)), axis=1)

return idx

In this generate function we are given an initial prompt and the number of tokens we want to generate. Then we do the following:

- Pass the initial prompt + any tokens generated till now to the model, and get model logits

- Based on the logits, sample the next token to be generated. Depending on the whether

temperatureandtop_kare given, we choose whether to rescale logits and whether to only sample from thetop_klogits instead of entire vocabulary. - Concatenate the new token to the sequence and repeat till we have generated

max_new_tokensnumber of tokens.

Features missing from this implementation

For simplicity we omitted some features in this implementation:

- KV-Cache: KV-Cache allows for caching during auto-regressive text generation, increasing compute efficiency significantly, you can learn more about it in the video here.

- Grouped Query Attention: This is a modification of multi-headed attention where for computational efficiency we share key and value heads across multiple query heads. You can check out this paper by Ainslie et al[6] for more details.

Conclusion

In this blog post we explored the architecture of Llama2, and learned how to implement key functionalities from scratch. We can see that in practice the architecture is a simple mixture of transformer blocks with regularizers and positional embeddings.

You can check out the complete source code at my github repo llama2.npy and run it locally by following the instructions.

References

- Touvron et al. “Llama 2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models” (2023)

- Andrej Karpathy, llama2.c (2023)

- Vaswani et al. “Attention is All You Need”, CoRR abs/1706.03762 (2017)

- Jay Alamar, “The Illustrated Transformer” (2018)

- Su et al. “RoFormer: Enhanced Transformer with Rotary Position Embedding”, CoRR abs/2104.09864 (2021)

- Ainslie et al. “GQA: Training Generalized Multi-Query Transformer Models from Multi-Head Checkpoints”, eprint 2305.13245 (2023)